2018 RNRG Book of the Year

A long time Beastie Boys pal celebrates the tome that tells it all

It’s a slightly odd feeling to know there are several hours of interview transcripts in a drawer (or, more likely, in the cloud) somewhere, detailing my early friendship with Mike D. – walking into his room and seeing his practice drums, all the records we listened to, his brother Stephen’s influence on us both, the Mercedes windshield we destroyed with a water balloon (Oops – I don’t think that’s in the interview! Anyway, we were caught and paid for our crime.).

Then there’s the founding of the Young Aborigines after I brought him and John Berry together (at a Joe Jackson concert – facts!), the months of practice, walking together dragging my equipment from my apartment on 101st, more talk about music. Always talk about music. Sometimes in our version of Jamaican patois – more on that later.

Also included is the segue into the Beastie Boys, after a brief period of overlap, and what lay ahead, including the cold April morning when I shot the cover of Paul’s Boutique. I don’t bring this up to aggrandize myself – living through it was exciting enough – but simply to point out that the mastery of selectivity is a huge part of hip hop and one that Michael Diamond and Adam Horovitz carry over to their latest project, Beastie Boys Book, which samples their storied past, creating a seamless read out of a wide variety of material. In the final edit, part of my story is there in Mike’s words, but there are others whose history with them is far more attenuated than mine.

Those interviews were conducted early on when the original idea was, I believe, to have an editor who would assemble entries from a number of different sources, including Diamond and Horovitz, perhaps in a form that would more resemble a scrapbook than the brick-shaped tome with which we are currently presented. In its final form, the book retains what may be some hangover from that old kernel of an idea, with essays and contributions from Luc Santé, Jonathan and Blake Lethem, Kate Schellenbach, Spike Jonze and others, but the overall authorial voice comes from Diamond and Horovitz. It’s also beautifully designed, with a hint of a Swiss modernist style, no doubt in tribute to Nathanial Hörnblower, the alter ego of fallen Beastie brother Adam Yauch.

Of course, Yauch’s missing voice is the white elephant in the book. They could have dealt with it the way The Beatles wove old John Lennon interviews and writings into the companion volume to The Beatles Anthology; instead they allow a portrait of MCA to develop via their own descriptions and reminiscences. It’s an effective and hauntingly accurate conjuring of the guy I knew, someone who could be simultaneously goofy and intense, spit-take funny and deeply insightful. Naturally, they can’t avoid shaping that portrayal partially as a way to make sense of the tragedy of Yauch’s death. The pull towards hagiography is strong when someone is taken from us too soon – the fact that they mostly avoid it is a tribute to their respect and love for him. As I’m writing that, I want to be clear that I have no issue saying Yauch was a special person, but also that cancer sucks and, goddamnit, he still had more work to do, including raising his daughter.

I can also say that I learned more about Yauch and the intra-band dynamic than ever before. Since I usually left when their rehearsals started and was soon not attending them at all, the amount of shoulder he put into moving the Beastie wheel along was not something I was aware of, and all the motivation and direction he provided is probably one of two or three main factors in the success of the group. When I saw Mike and Adam at the opening night of their Beastie Boys Live & Direct book tour, I could see they were making an effort to develop a new collective persona as a duo. Having now finished the book, I can only empathize further with what they had to do – and the bravery it took – to make that all work. I can also say that their interplay, with Mike as the slightly absent-minded ideas guy and Adam as the borderline OCD sufferer trying to keep things on time and on track, was very funny and relatable.

Besides expanding my vision of who Yauch was and what he made happen, I really had the most to discover about Ad-Rock. I had certainly met him before he joined the Beasties but, while there wasn’t any bad blood, I can’t say we hit it off. I even remember a funny moment when my college band was rehearsing in one of those rent-a-cell rehearsal mills in the west 20’s and I realized The Young & The Useless were right next door. They were hard to miss – even my guitarist, who had no idea who they were, said something like, “Jeez, those kids are annoying!” So I was fascinated to read about his snap decision to buy a Roland TR-808 instead of another guitar, a drum machine he quickly mastered to the point of programming the rhythm track on LL Cool J’s first single, “I Need A Beat.”

It was also moving to read about the moment during the recording of “Picture This” from Hello Nasty when he had the following revelation: “This is another song that I played all the instruments on, down in the dungeon. I’m not telling you that because I’m full of myself. I am, but that’s beside the point. What I’m saying is…and I know it may sound weird, but it took me a really long time to admit to myself that I was a musician. Making music by myself by myself in the dungeon by myself is what, in my mind, transformed me from just being a guy in a band to being someone who’s confident when writing the word “musician” next to the word “occupation” on a piece of paper.”

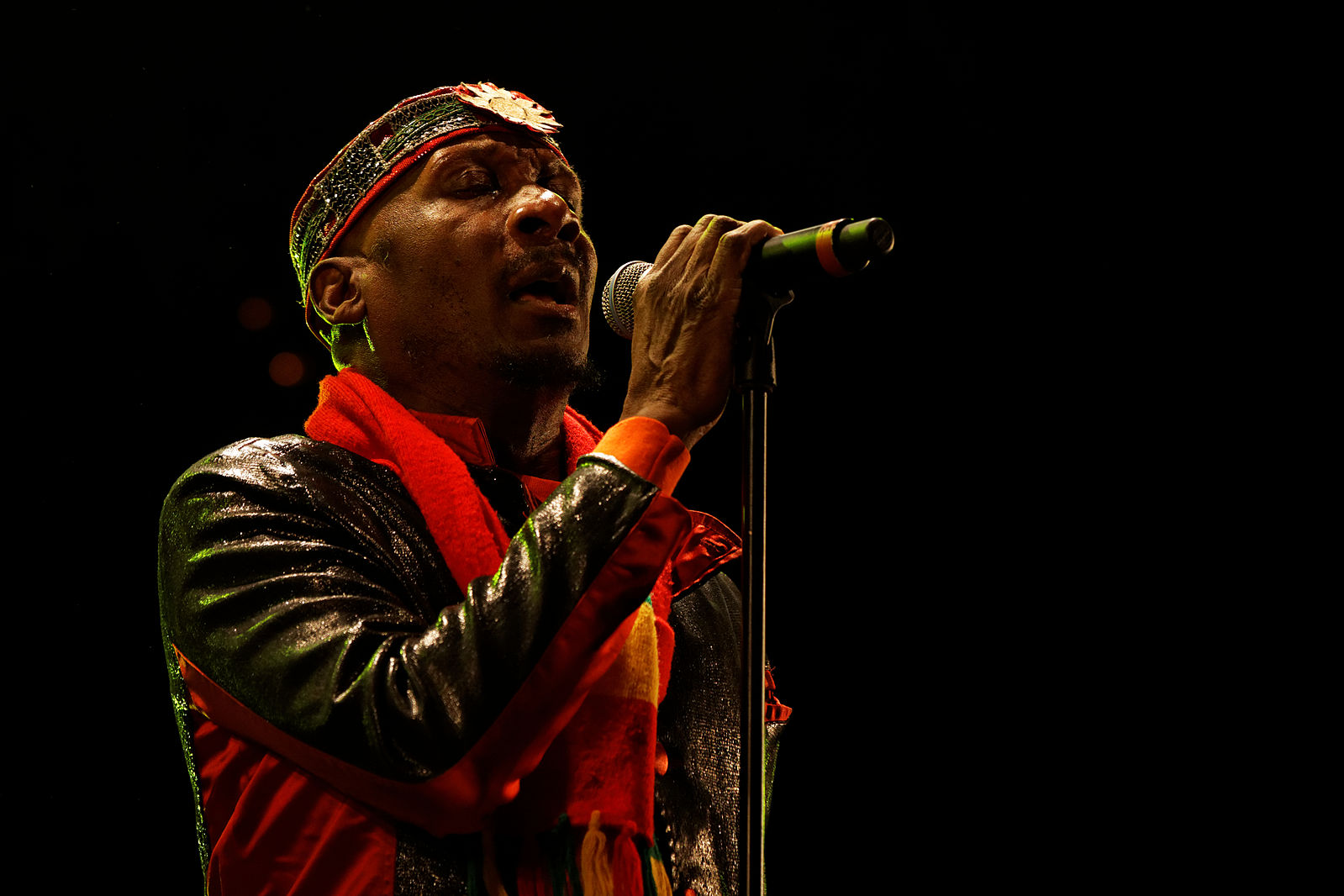

Ad-Rock’s whole relationship with music was a bit of a revelation to me. His obsessive description of his own version of cassette culture reminded me of my own, although his covers were way better than mine – “You couldn’t just have the white TDK sleeve with song titles,” he proclaims, although Mike and I rarely did anything else. If you want to learn about Mike’s approach to the mixtape (or “pause tape” as we never called it then), you’ll have to read another book, For Whom The Cowbell Tolls by Dan LeRoy, in which I revealed all about his fascinatingly slapdash approach to putting songs on tape. (Warning: “P. Cicero” on Amazon says the info on “Mike D.’s old mixtapes leaves me no interest.” Past performance is no guarantee of future results.) Even Adam’s taste was better than I thought – geeking out on Lee Perry is one of my favorite pastimes, and one I didn’t know we shared.

This more dimensional picture of Horovitz left me with a curiously melancholy aftertaste. His deep love of music, the expertise at putting tracks together, his ability to turn in a classic “classic-rock” vocal performance like “Sabotage” – all of it went completely underground after Yauch died and shows no signs of reemerging. That’s perfectly understandable, especially in the immediate aftermath, and he’s explored other creative pursuits, becoming a very good actor in the process. But I found myself recalling that video from Sway In The Morning that made the YouTube rounds a few years ago, which had Adam relating that he doesn’t listen any new music. Clearly, the issues go deeper than the loss of his friend, and as someone who spends most of his time listening to only new music, I wanted to reach out a hand to my old acquaintance and bring him back into the fold.

While Yauch’s transformation from punk rocker and party starter to thoughtful philanthropist is well known, the fact is that Horovitz grew up into the mensch he is may be as dramatic a change. Mike has grown as well, delivering one of the finest short essays in the book in his remembrance of The Captain, a guy I found too strange to connect to, but about whom I now have a whole different idea. Horovitz is equally compassionate describing the quixotic journey of Dave Parsons, who released the first Beastie Boys EP on his Rat Cage Records. And letting us know of Yauch’s financial support for Parsons’s sex-change operation is another humbling reminder of his unique spirit.

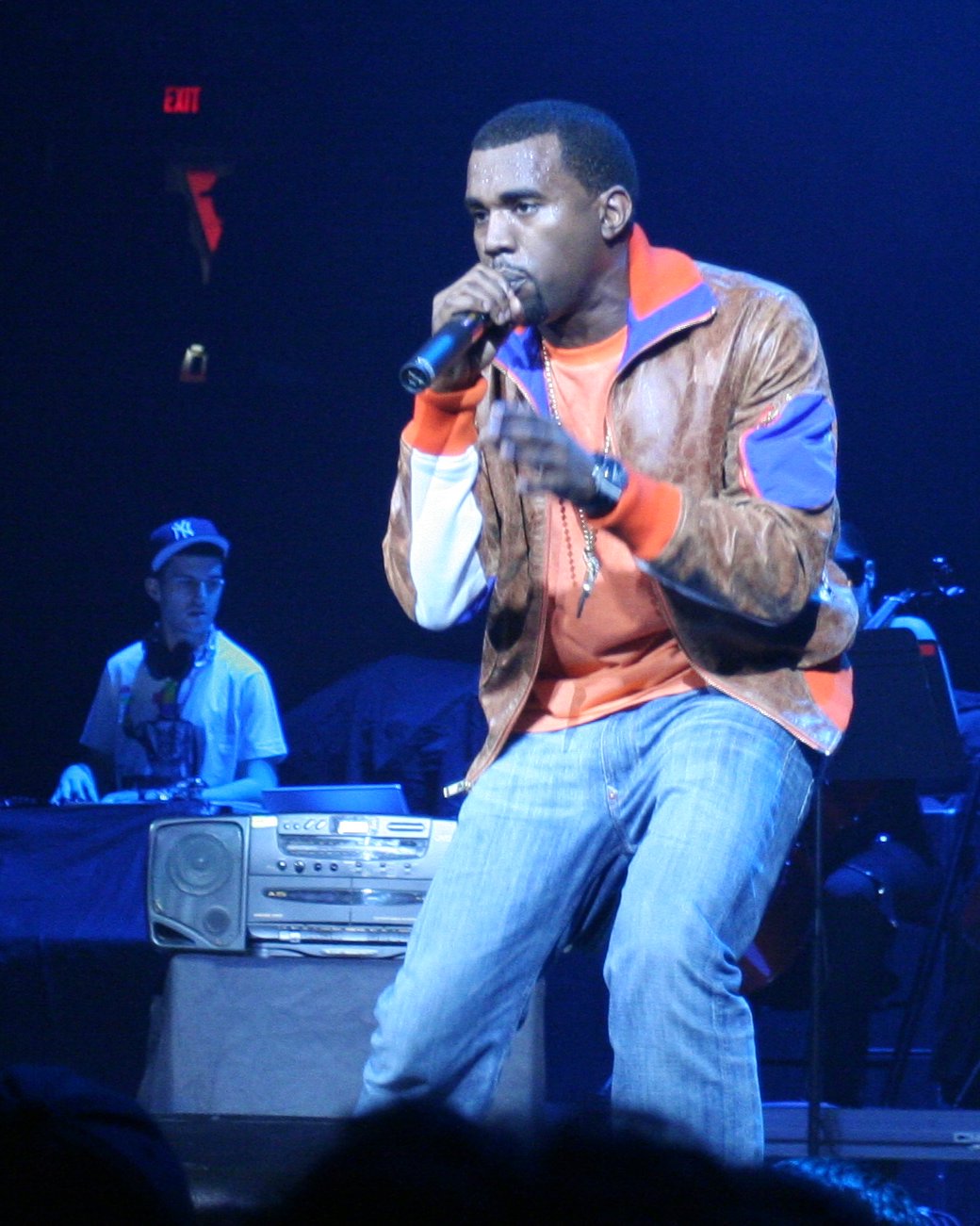

These descriptions of people important to their early years making music and getting on the road are rich with detail and full of feeling, but only make it odder that D.J. Hurricane does not even really exist as an individual in the book. Ten years plus behind the decks with the Boys earns him a name-check as one of a “Spinal Tap-ish run of DJs,” a brief mention during a disastrous show at Power Tools in LA, and the inclusion of his album The Hurra in a list of Grand Royal releases. There’s a story there, and Hurricane himself is probably too much of a sweetheart (if his appearances at past MCA Day events are any indication) to address the iniquity. The issue certainly couldn’t be length as they make room for a Lethem’s slightly pretentious chapter about white people, summer camp and hip hop culture, not to mention several pages of recipes by super-fan and super-chef Roy Choi (OK, I will make the Get It Together BBQ Grilled Cheese), but Hurricane has no say. Not the classiest move, especially when you consider the credibility lent by Hurricane back in the day, with his deep connections to the Run DMC orbit.

I’m someone who believes there is no culture without “cultural appropriation” – hence talking in patois, wearing a dashiki during the Young Aborigines only two concerts, falling deeply into what we used to call “black music” – but now we have the smarts and sensitivity to acknowledge the roots from whence what we’re doing arises. There is little of that kind of exploration in the book, except to say of one hip-hop song or another, “We fucking loved it.” When I think about my relationship to hip-hop, I look within and connect to my own experiences feeling like an outsider (hat tip to Big Rube: “Are you an OutKast? I know I am.”), not to mention the sense of being a survivor of the urban jungle, as I walk the streets with Public Enemy or Mobb Deep booming in my ears. There’s also the cerebral fascination with making records from other records, the adrenaline hit of the perfect, yet unexpected, jump-cut between styles. I wouldn’t have minded a little of that kind of self-examination in Beastie Boys Book.

There are hundreds of fascinating nuggets about their artistic development, however, such as Mike’s description of how he overcame his nearly crippling shyness to be a frontman in a band: “I was usually pretty shy and quiet, so to be yelling lyrics into a mic felt deeply foreign. I remember looking down at the floor a bunch because I wanted to make as little eye contact as possible. But what I quickly discovered about singing was this: it’s a different part of you. It’s not like me having an actual conversation with you, or me being in a taco restaurant nervously trying to say hi. You’re in a totally different context, and it’s a band, you know — so it’s kind of like a gang. You don’t want to be afraid and, pretty soon, you’re not.” I wish my mom were around to read that – she used to always say, “HE’S on stage? He can’t even look me in the eye and he always mumbles when he says hello!”

There’s also that time in Rick Rubin’s dorm room when he pushes the Boys to develop their individual personalities on the mic, telling Mike that he “needs to sound like he’s working hard when he raps.” For Yauch, “rapping was effortless, and it sounded like it. Yauch was a natural. He could effortlessly spit out a flawless re-creation of Spoonie Gee or Frederick MC Count.” In an aside, Ad-Rock chimes in that he wanted to sound like Jimmy Spicer, “But after hearing myself on the mic with a fake deep voice…I had to come up with something different. Something that was more me. I had to admit that I’m not a low-voiced smooth talker. I’m more the whiny, upset, screaming type. So the adjustment was made, and I felt way more comfortable on the mic.”

The details of finding their musical voice with “Hold It Now, Hit It” are even more captivating and the succession of happy accidents and bold choices that led to their early success are both hilarious and exciting. They rose with Licensed To Ill, amassing a massive audience that sometimes freaked them out. Then they fell (commercially, anyway) with Paul’s Boutique – mainly thanks to what can technically be called “stupidity” on the part of Capitol Records, which seems even dumber when you consider the beautiful production values they put into our groundbreaking 360 cover. Then we get the adventure of rebuilding and widening their audience with Check Your Head, along with fascinating details about their pioneering internet presence thanks to an excellent chapter by Ian Rogers, the founding of Grand Royal, which helped make things right with Schellenbach when Luscious Jackson became successful. Once the book enters the zone beyond Check Your Head, though, some material starts to seem gratuitous. I want to tell Ad-Rock, “The first time you almost OD on “space cookies” is a rookie mistake – the second time, well, that’s just a mistake.” Also, after Mike and Adam spend much of the book trading chapters, Mike disappears in the last third of the book, with 10 chapters in a row credited to Horovitz. Thankfully, one of those chapters is “The Ring,” the awe-inspiring tale of a 15-year prank pulled by Yauch. They really did break the mold when they made that guy. There’s a picture of him crowd-surfing while rapping furiously at the first Tibetan Freedom Concert that I must have stared at for 10 minutes straight, just one of many astonishing images in the book.

In the end, like many of the Beastie’s albums, what’s lacking in editorial oversight is more than overcome by their freakishly quick-witted sense of humor and their all-embracing love of music. There is reference to so many mind-blowing sounds in this book that it was a joy just letting it all play in my head. Bad Brains, Os Mutantes, Can, Linton Kwesi Johnson, Jimi Hendrix, Bob Dylan, not to mention all the hip hop heat – you could make endless playlists just following up on everything they mention and have one of the best collections in the world. Put it all on a golden record, shoot it up into space and let the aliens know what we humans can really do! Get a taste by searching “Adam Yauch Playlist – Beastie Boys Book” on Spotify, then put in the work and make your own mixtapes.

I also listened to the audiobook and it’s a pretty wild ride, even if the expense of music-licensing means you won’t hear any of those classic tracks on there – even from the Beastie Boys’s own albums. Both Diamond and Horowitz are quite fine as readers, with styles as individualistic as their rapping, but they break up their contributions with recordings by everyone from Chuck D. and Kim Gordon to Rosie Perez and John C. Reilly. Some of the guest readers seem like little more than a flagrant demonstration of Mike and Adam’s not inconsiderable celebrity pull, but I can’t deny my delight at hearing Gordon pronounce my name as “satin” in her velvety downtown drawl. Whatever the future holds for Diamond and Horovitz, or their band, with Beastie Boys Book they have put a perfect capstone on their trajectory from hardcore pseudo-anarchists to hip hop insurrectionaries and finally to elder statesmen and icons of cool. And I’m proud as hell of them for doing it.